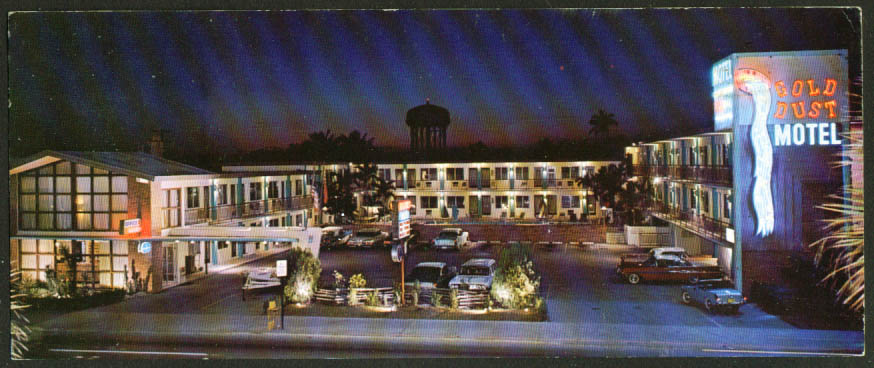

GOLD DUST

Gold Dust Motel, c. 1950's, Historic Postcard

II. SIGNIFICANCE

Specific Dates:

1957

Architect:

Maurice S. Weintraub

Builder/Contractor:

Shafer and Miller

Statement of Significance:

The Gold Dust is architecturally and culturally significant as an exemplary 1950s MiMo (Miami Modern) motel and as a prominent work by profilic Miami architect Maurice S. Weintraub. As the development trends of Greater Miami advanced during the mid-twentieth century, MiMo architecture along the Biscayne Boulevard corridor became noteworthy for incorporating elements which reflected the post-World War II automobile culture. It is also notable for its details, materials and craftsmanship, as reflected in its U-shaped building footprint, open-air verandas with catwalks, roman brick detailing, elevated trapezoidal pool deck, jet-age porte-cochère, and distinctive monument signage. Gold Dust is one of the most important examples of a 1950’s MiMo motor courtyard motel on Biscayne Boulevard.

The prominence of Biscayne Boulevard as a principal north-south thoroughfare began in 1925 with the connection of Miami Shores to downtown Miami by two developers, Hugh Anderson and Roy C. Wright. An economic downturn shortly after forced the transfer of the visionary project to Henry Phipps of U.S. Steel. The consumer car culture of the 1950s converged with another boom development period in the “Magic City” and motor courtyard motels started to populate the boulevard during this expansion period. Additionally, this era marked a new fashion in building design which incorporated “jet-age styling” and advanced materials. The structure was completed on December 21, 1957, and maintains much of its original structure and integrity. Serving intially as a motel, travelers visiting Miami were provided “luxury living at its finest—and at sensible prices.”[1] Under new management, the historic rehabilitation will conform to the Secretary of Interior Standards, and continue the MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard local historic district as an individual landmark.

[1] “Grand Opening,” Miami Herald, December 21, 1957

As the development trends of Greater Miami advanced during the mid-twentieth century, MiMo architecture along the Biscayne Boulevard corridor became noteworthy for incorporating elements which reflected the post-World War II automobile culture. Gold Dust is one of the most important examples of a 1950’s MiMo motor courtyard motel on Biscayne Boulevard.

Relationship to Criteria for Designation:

As stated above, the Superior Apts has significance in the historical and architectural heritage of the City of Miami; possesses integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling and association; and is eligible for designation under the following criteria:

(3) Exemplify the historical, cultural, political, economical, or social trends of the community;

Following the outbreak of World War II, Greater Miami became a major training center for the Armed Forces. The end of the war brought an influx of people, including former soldiers, and expansion along Biscyane Boulevard continued northward and westward. Consequently, Greater Miami experienced a post-World War II boom. For the first time, automobiles were a dominant consideration in city planning and architectural programming. Businesses, resorts, and motels along major thoroughfares catered to the speed and ease of traveling by car. It was in this climate that Gold Dust was developed, capitalizing on its central location along Biscayne Boulevard near the 79th Street thoroughfare, allowing motel guests access to the beaches east and to the Hialeah Park Racetrack west.

(4) Portray the environment in an era of history characterized by one or more distinctive architectural styles;

Gold Dust embodies characteristics of the MiMo (Miami Modern) style which was popular from 1945 to the mid-1960’s.[1] It represents a motel interpretation of Subtropical Modernism, an adaptation of The International Style to the local climate, with kitschy “Old West” detailing to differentiate the structure.[2] Gold Dust capitalized on the booming post-World War II tourism economy, providing a cost-effective vacation for America’s middle-class population, reflected in its interpretation of MiMo architecture.

(5) Embody those distinguishing characteristics of an architectural style, or period, or method of construction;

Gold Dust is an excellent example of the application of the post-World War II MiMo (Miami Modern) style of architecture to the South Florida environment. The building is particularly noteworthy for its “Old West” references, monument neon signage, Wrightian references of an open gable roof and built-in planters, jet-age porte-cochére, roman brick details, open-air verandas with catwalks, floating staircases, and U-shaped building footprint. The monumental neon logo was prominently placed on the north sign wall with an additional sign pole in the center in order to attract the attention of passing motorists. The eastern parking courtyard reflects the era’s motor-age sensibilities towards tourism, transportation, and technology. The elevated trapezoidal pool deck remains one of the last extant examples on Biscayne Boulevard, reflecting the importance of marketing the tropical appeal of Miami to visitors from less exotic climates.

(6) Is the outstanding work of a proimnent designer or builder.

Gold Dust was designed by prolific Miami architect Maurice S. Weintraub. He designed many prominent local projects varying from private luxury residences and commercial properties in Coral Gables, Coconut Grove, Surfside and Miami Beach including The Moorings in Skylake, the Golden Strand Hotel on Miami Beach, the Royal Biscayne Hotel on Key Biscayne, The Forge restaurant in Miami Beach and the David Williams Hotel in Coral Gables.[3] In the same year, he completed the Admiral Vee hotel a few blocks north at the intersection of 79thStreet and Biscayne Boulevard.[4] He also designed numerous international projects.

[1]Nash and Robinson, MiMo: Miami Modern Revealed, San Francisco: Chronical Books, 2004, 9.

[2]“Grand Opening,” Miami Herald, December 21, 1957. MiMo is characterized by a particular time and place, within the subtropical South Florida environment, rather than a single style.

[3]“Obituary,” Miami Herald, August 8, 2007.

[4]Castillo, Greg, “Speedreading Biscayne Boulevard,” Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009, 220.

III. HISTORICAL INFORMATION

Date of Construction:

1957

Architect:

Maurice S. Weintraub

Builder/Contractor:

Shafer & Miller

Historical Context:

Prior to major road infrastructure expansion, the area of Lemon City, one of the first areas settled in Miami, was known as a “farm trade town with a lively port” through the late-19thcentury.[1] In 1892, the county constructed the first railway from Lemon City to Lantana, and development expanded on both sides of the tracks. The development of Biscayne Boulevard in the 1920s was an expansion of necessity to conenct the northern suburb of Miami Shores south to downtown Miami. The Shoreland Company needed to provide a direct link to entice buyers of both the ease of access downtown and the attractiveness of the development’s tropical haven. During the boom of the 1920s, resort hotels influenced by Flagler’s Royal Palm Hotel were erected in the downtown portion of Biscayne Boulevard.[2] By 1925, Lemon City was annexed into the City of Miami.

Due to an economic downturn in 1926, the project halted but subsequently persisted under the direction of Henry Phipps of Bessemer Properties.[3] (Figure 1) In the 1925 Hopkins map, the suburbs of Shorecrest are delineated to the north and Baywood to the south, however nothing existed yet on the property site, except ownership by “Ullendorf.”[4] As a member of the Biscayne Boulevard Assocation, Phipps encouraged a new “Main Street of Greater Miami.” By 1927, over thirty blocks and an investment of an estimated six million dollars by the City of Miami were utilized to widen the new thoroughfare.[5] In 1929, the North Bay Causeway over Biscayne Bay opened and aligned with 79thStreet, linking Miami Beach to Miami. Established by developer Henri Levy, it’s completion coincided with the popularity of the Hialeah Park Race Track, coupling “hostelries and wealthy winter residents with the racetrack and betting.”[6] Biscayne Boulevard became a convenient adjacencies between the two attractions.

As the “Magic City” continued to flourish, Miami’s interpretation of The International Style, “MiMo” (Miami Modern) began to define the architectural fabric of Biscayne Boulevard. Florida’s population grew by over eighty percent by the end of the 1940’s. (Figure 2) In addition to a recovering economy, paid vacations and Social Security benefits became beneficial post-World War II innovations for South Florida.[7] Biscayne Boulevard, also known as U.S. Highway 1, became a crucial node for motorists arriving on vacation, and grew into the main north-south route from Maine to Key West. Most prevalent were the “typical roadside motels,” adapted to the tropical climate, centered around a motor courtyard in order to celebrate the arrival of guests by automobile.[8] Though these motels catered predominately to middle-class tourists, architects creatively maximized their street presence with “jet-age styling,” monumental neon signage, and unique themes to catch the attention of passing cars at any speed.[9] The urban lots along Biscayne Boulevard were smaller in dimension, as compared to their Miami Beach resort counterparts. Dense concentrations of MiMo architecture developed in a unifying style to compliment northern and western suburban expansion.

In 1957, the design of architect Maurice S. Weintraub at the Gold Dust Motel was completed.[10] Just a few years earlier, in 1954, the Biscayne Plaza Shopping Center a few blocks north at the 79thStreet intersection opened.[11] This created a contemporary epicenter for residents and tourists to gather north of the downtown core. Weintraub designed many prominent local projects varying from private luxury residences and commercial properties in Coral Gables, Coconut Grove, Surfside and Miami Beach including The Moorings in Skylake, the Golden Strand Hotel on Miami Beach, the Royal Biscayne Hotel on Key Biscayne, The Forge restaurant in Miami Beach and the David Williams Hotel in Coral Gables.[12]

With the prevalence of automobiles, access to the “city’s new suburban downtown” and its commercial districts allowed visitors to venture past downtown to enjoy cost-effective vacations.[13] The importance of the automobile in post-World War II America changed the speed at which people could not only navigate Miami and the beaches, but also influenced the built environment from urban planning contexts to the individual development of MiMo architecture. Accessibility of global air travel at Miami International Airport and a developed Interstate system broadened access to the city. This was a significant advancement in the advertisement of cost-effective vacations for people of diverse backgrounds.

The arrival of the property was anticipated and celebrated with fanfare.[14] (Figure 3) Constructed as a 66-unit motel, with 26 efficiencies for longer-term guests, Stuart Gray of Gray’s Electric developed the well-located property, “with 183 feet on Biscayne Boulevard, 175 feet deep and bounded on the north by a waterway.”[15] The grand opening promised “Ultra Modern Living…In a setting of the Old West,” on December 21, 1957.[16](Figure 4) The motel featured a cocktail lounge and coffee shop, as well as entertainment from the pool to the lounge. Economy and comfort were established in the grand opening ad which proclaimed, “… finest furnishings complete with television… fully air conditioned and heated for year-round comfort.” Air conditioning was introduced as a novel modern convenience which enhanced to the comforts of living in South Florida, also supporting a yearround economy.[17] The pool, once reserved for the grandest resorts, became a symbol of luxury in an accessible post-World War II environment.[18] Activity was centered around the pool and provided a backdrop for the modernist architecture. Additionally, the Grand Opening ad boasted features including a conference room, dockage for boats, and hand-painted murals.

Where many MiMo architects found inspiration in futuristic designs and the technology of automobiles and airplanes, Weintraub utilized themes of the “Old West” to differente the Gold Dust from neighborhing competitors. (Figure 5) Motifs typical to MiMo architecture included a monumental neon sign wall, porte cochére stylized with acute angle wings, pole sign to provide a dynamic entrance for the automobile, open air verandas with catwalks, exterior floating staircases, roman brick detailing, and an elevated trapezoidal pool deck to maximize the enjoyment of the tropical climate. The influence of Frank Lloyd Wright introduced Prarie-style elements including a gabled roof, use of roman brick to emphasize horizontality, and built-in planters.

By 1958, the Gold Dust Motel began to advertise apartments as “Brand New Large efficiencies $125 month ($1,079 in 2018) and 1 bedroom Apts. $150 month ($1,295 in 2018).”[19] (Figure 6) Adding “Apts” to their name, the motel promised “100% air conditioned, all utilities, wall to wall carpeting, daily maid service, pool, switchboard, lounge, coffee shop, game room.” By 1962, commercial reservations “for commercial men only” were advertised for $6 year round ($50 in 2018).[20] (Figure 7) Lodging to entertainers at the nearby Playboy Club provided notoriety for the Gold Dust.[21] During the mid-1960’s, classified ads demonstrated the need for barmaids at the lounge, the availability of the coffee shop for lease, and the continued advertisement of efficiencies for rent.[22] (Figure 8) The property continually adapted through the 1960’s, eventually adding an additional lounge, beauty salon, and private commercial space. (Appendix A)

Urban renewal of the 1970s led to decay and disrepair along Biscayne Boulevard. Significant alterations to the exterior included stone cladding and brick veneer additions, a “Gold Dust Motel” sign along the gable roof ridge, a northeast appendage of the restaurant entrance and a southeast addition of a chamfered corner to provide additional commercial space.[23] (Figure 9) Abandonment and significant infill development led to the preservation and nomination of the MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard Historic District in 2006.[24]

[1]Mahoney, 17.

[2]Nash and Robinson, 22; Royal Palm was razed in 1931.

[3]Castillo, Greg, “Speedreading Biscayne Boulevard,” Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009; The Phipps family controlled the interest of U.S. Steel.

[4]G.M. Hopkins, Plat Map of Greater Miami and Suburbs, Philadelphia: 1925.

[5]“Miami Finishing $6,000,000 Highway, New York Times, January 9, 1927.

[6]Nash and Robinson, 25.

[7]Ibid., 14.

[8]U.S. Highway 1 became the main north-south route from Maine to Key West. Ibid., 26.

[9]City of Miami, MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard Historic District, 2006.

[10]“Grand Opening,” Miami Herald, December 21, 1957

[11]Castillo, Greg, “Speedreading Biscayne Boulevard,” Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009, 220.

[12]“Obituary,” Miami Herald, August 8, 2007.

[13]Nepomechie, Marily R., “Biscayne Plaza: Miami’s First Suburban Shopping Center,” Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009.

[14]“There’s Gold on Boulevard,” Miami Herald, June 30, 1957.

[15]Ibid.

[16]“Grand Opening,” Miami Herald, December 21, 1957.

[17]Nash and Robinson, 14.

[18]Ceo, Rocco and Allan T. Shulman, “Priviledged Views and Underwater Antics: Swimming Pools, Diving Towers & Cabana Colonies, Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009.

[19]“Advertisement- Brand New,” Miami Herald, September 6, 1958.

[20]“Advertisement – Commercial Reservations,” Miami Herald, March 30, 1962.

[21]Bourke, George, “Nightlife – Melodye’s Act It’s a Duo,” Miami Herald, March 25, 1962.

[22] “Advertisement – Efficiencies Large Motel,” Miami Herald, September 13, 1963; “Advertisement – Coffee shop available,” Miami Herald, January 16, 1963; “Advertisement – $100 Week Guarantee,” Miami Herald, November 12, 1964.

[23]Referenced from tax card image and 1976 Miami Herald image.

[24]City of Miami, “MiMo Biscayne Boulevard Historic District,” 2006.

IV. ARCHITECTURAL INFORMATION

Description of Building:

Gold Dust is a U-shaped structure wrapped around a central motor courtyard with a porte cochére. The structure contains multilevels of stepped intervals over two stories and varies in first floor heights to provide visual differentation to all three facades. The motel rooms are composed as single rooms and efficiency layouts. Though there are other examples of MiMo motels preserved along Biscayne Boulevard, the Gold Dust is one of the last remaining with its original elevated trapezoidal pool deck intact.

All three wings of the building are connected by a tiled raised concrete platform, with catwalks facing the interior motor courtyard. Typical to MiMo architecture, the passageways provide an effective means of exterior corridors and circulation. The pedestal-and-tower motif was adapted by MiMo architects to provide a distinctive South Florida resort style composition. The interior and exterior blending of space to capitalize on South Florida’s hot-humid climate was characteristic of the Subtropical Modernism design.

The stylized monumental sign wall and pole sign at the west entrance were designed to entince passing motorists. Though currently altered, both signs represented the sense of playful vacation which attracted weary drivers into the property off Biscayne Boulevard/U.S. Highway 1 thoroughfare. Identified by an animated scene of siffting gold or “gold panning” on the historic wall sign on the northeast corner, Gold Dust established a significant presence on the boulevard.

The jet-age stylized porte cochére communicated a sense of arrival. The differentiation of the acute angles within a strictly modernist template were also echoed on the trapezoidal mosaics on the northeastern façade. Though restrained in design, the use of roman brick to highlight the main façade provided a horizontality popularized by the Prarie Style movement of Frank Lloyd Wright. Built-in planters communicated the transition from the rectilinear modernist architecture to a naturalized environment, landscaped with “western” cacti groupings among the expected South Florida palm trees.

The southeastern gabled roof emphasized themes of the prototypical American home at a loftier scale. Plate glass articulated over the two floors were intersected by the wing of the porte cochére. Representative of the technology developed during the International Style, the steel-sketelon construction allowed maximum light into the lower lobby and additional spaces above. Additions to the structure in the 1960s have been maintained in the current footprint. The restaurant enclosure on the northeast corner was added in 1961. (Figure 10) The chamfered corner and additional entrance at the southeast corner were added in 1966. (Figure 11) A prominent sign over the center gable was also added, but removed.

The concrete block and stucco walls on the interior-facing facades were articulated with pilasters to emphasize the separation and indepence to room entrances. At one point the façade was covered in the 1970s with a textured stone, but was removed at some point. (Figure 9) The continuity between interior and exterior space remain articulated in the floating staircases and catwalks. The space-age delineation of the semi-floating staircases were typical of MiMo architecture.

There are elements that have been altered or updated since it was originally constructed. However, the resource still retains integrity and exhibits major character-defining elements of MiMo motel architecture.

Description of Site:

The Gold Dust is located on the western side of Biscyane Boulevard bound by NE 77thStreet to the south and Little River to the north. The main entrance is on the west side of the property at Biscayne Boulevard. The courtyard and parking lot face Biscayne Boulevard. The structure faces commercial buildings to the east and south, and a low-density neighborhood to the west. Most notably, Gold Dust contributes to the architectural history and legacy of MiMo motel structures on Biscayne Boulevard.

V. PLANNING CONTEXT

Present Trends and Conditions:

Gold Dust is an excellent example of an “Old West” interpretation of the MiMo style in the City of Miami. With its original use as a motel with efficiency apartments, its preservation as a motel maintains its use and a majority of the authentic architectural elements. Though previously excluded from the MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard local historic district, Gold Dust is an excellent example of preserving post-World War II MiMo motel architecture along the Biscyane Boulevard corridor.

Preservation Incentives:

Over the years, the Gold Dust has been altered and continued to deteriorate. The property will undergo a substantial historic rehabilitation to restore its original character-defining features. It is a unique example of the development of the MiMo architectural style along the important Biscayne Boulevard corridor. Any future alterations or additions should respect its historic character.

Through historic designation, the property will be eligible for TDRs (Transfer of Development Rights). Due to its favorable T6-8-O zoning, the substantial investment needed to restore the original features to the Gold Dust would be partially funded. In addition, the increased property tax resulting from a higher assesed value could be deferred for a period of 10 years under the Miami-Dade County ad valorem tax incentive ordinance. The property will also likely seek nomination to the National Register of Historic Places due to the substantial renovation needed, and would be eligible for the 20% Federal Historic Tax Credit.

If the City of Miami adopts the Florida State Statute Section 196.1961, which allows a 50% reduction in an historic property’s assessed value, this will further the objectives of the project as an historic rehabilitation that contributes to the economic development and resurgence of Biscayne Boulevard. An interpretation of this statute was recently adopted by Miami-Dade County at a 25% tax reduction.

The designation of Gold Dust will not only continue the MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard local historic district north, but can act to encourage a National Register nomination for the corridor as a whole. While establishing a context for future development and sustainable growth, its designation as a historic resource will help preserve the area’s cultural heritage and architectural fabric for future generations.

VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Advertisement – $100 Week Guarantee,” Miami Herald, November 12, 1964.

“Advertisement- Brand New,” Miami Herald, September 6, 1958.

“Advertisement – Coffee shop available,” Miami Herald, January 16, 1963.

“Advertisement – Commercial Reservations,” Miami Herald, March 30, 1962.

“Advertisement – Efficiencies Large Motel,” Miami Herald, September 13, 1963.

Bourke, George, “Nightlife – Melodye’s Act It’s a Duo,” Miami Herald, March 25, 1962.

Castillo, Greg, “Speedreading Biscayne Boulevard,” Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009.

Ceo, Rocco and Allan T. Shulman, “Priviledged Views and Underwater Antics: Swimming Pools, Diving Towers & Cabana Colonies, Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009.

City Directory. City of Miami, 1953-54, 1956, 1957, 1958-59, 1960, 1962, 1964, 1966, 1967, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1973, 1974-75.Located at HistoryMiami archives.

City of Miami, “MiMo/Biscayne Boulevard Historic District,” 2006.

D’Amico, Teri and David Framberger, editors. Beyond the Box: Mid-Century Modern Architecture in Miami and New York. Urban Arts Committee: Miami Beach, 2002.

Dunlop, Beth. Miami: Trends and Traditions.Monacelli Press: New York, 1996.

Faus, Joseph. “Lemon City was cradle of Dade’s Culture,”The Miami Herald.April 3, 1955.

“Grand Opening,” Miami Herald, December 21, 1957.

Hine, Thomas. Populuxe. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1986.

Hopkins, G.M., Plat Map of Greater Miami and Suburbs, Philadelphia: 1925.

Kleinberg, Howard. Miami: The Way We Were. The Miami Daily News: Miami, 1985.

LeClaire, Jennifer. “Miami Modern, or MiMo, Making a Big Comeback,” Architectural Record, December 1, 2004.

Leyden, Charles S. “How Lemon City Got Its Name,” Miami Daily News, October 31, 1949.

Mahoney, Larry. “Lemon City: Yes, Virginia, there is more to Miami’s past than Coconut Grove,” Miami Tropic, May 6, 1977.

Metropolitan Dade County Office of Community Development (MDCOCD). From Wilderness to Metropolis: The History and Architecture of Dade County (1825– 1940), 2nd Ed.Historic Preservation Division: Miami, 1992.

Nash, Eric P. and Randall C. Robinson, Jr. Mimo: Miami Modern Revealed.Chronicle Books: San Francisco, 2004.

Newman, Cathy. “Traces of Lemon City’s Past Lives On,” The Miami News, March 3, 1974.

Nepomechie, Marily R., “Biscayne Plaza: Miami’s First Suburban Shopping Center,” Miami Modern Metropolis, Miami Beach: Bass Museum of Art, 2009.

“Obituary,” Miami Herald, August 8, 2007.

Pancoast, Russel T., and James Deen. A Guide to the Architecture of Miami.American Institute of Architects, South Florida Chapter: Miami, 1963.

Parks, Arva Moore. Miami: The Magic City.Centennial Press: Miami, 1991.

Parks, Arva Moore and Carolyn Klepser. Miami: Then and Now. Thunder Bay Press: San Diego, 2002.

Patricios, Nicholas N. Building Marvelous Miami.University of Florida Press: Gainesville, 1994.

Peters, Thelma. Lemon City: Pioneering on Biscayne Bay, 1850-1925. Banyan Books: Miami, 1976.

Peters, Thelma.Lemon City Tour Guide.Dade Heritage Trust: Miami, 1981.

Standiford, Les. Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Railroad That Crossed an Ocean. Crown Publishers: New York, 2002.

“There’s Gold on Boulevard,” Miami Herald, June 30, 1957.

Written and researched by Laura Weinstein-Berman